Welcome to issue #14 of Indiscrete Musings

I write about the world of Cloud Computing and Venture Capital and will most likely fall off the path from time to time. You can expect a bi-weekly to monthly update on specific sectors with Cloud Computing or uncuffed thoughts on the somewhat opaque world that is Venture Capital. I’ll be mostly wrong and sometimes right. Views my own.

Please feel free to subscribe, forward, and share. For more random musings, follow @MrRazzi17

I’ve been obsessed with deciphering how early-stage startups win at the earliest of stages when there is so much randomness (i.e., luck) at play and nominal data by way of customers, usage, or anything else measurable that would indicate true product-market fit (PMF). What I love about early-stage venture and what tends to be the hardest thing about it is often N^1 examples don’t apply (e.g., if it worked for X, the company will work for Y) and how truly every company should be assessed uniquely on a set of specific new attributes—though at later stages, whether the B or C, these metrics are easily defined. One of the most perplexing things I’ve come across so far in my short tenure as an investor is assessing startups in hypercompetitive markets where product differentiation is nominal, traction is pretty much the same (relative to competition), the value proposition is the same, and at surface value —the founder heuristics match their competitors, setting aside variables such as assessing the founder's ability to execute—are there any real attributes to determine how to pick a winner in a competitive market?

Simply said, the world—notwithstanding startups and venture—is full of noise. Pulling out accurate signals is increasingly tricky amid such exponential randomness. As an avid reader, I realized there are parallels between startup randomness and books. There are thousands, if not millions, of books printed each year, but for the most part, the classics are often re-read and re-read, including Homer, which is more popular today than when it was originally written. The longer something has been around, the better chance it has of survival. In the context of venture and startups, merely being around long enough vis-a-vis, raising larger rounds, and bootstrapping to longevity increases the odds of survival. Perhaps if you’re a database company that raised $100M instead of $10M, large enterprises will perceive you as the safer option, considering you have more runway, thus making it easier to move petabytes of data. Survival is safety and perception at the same time. Conceptually, this is called the Lindy Effect.

Lindy Effect Primer

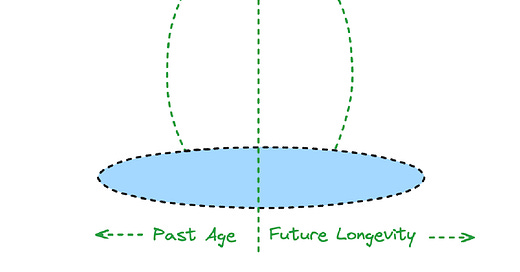

The Lindy effect, often referred to as Lindy's Law, suggests a unique correlation between the age of non-perishable entities, such as ideas or technologies, and their expected future lifespan. Essentially, this concept argues that the durability or usage span of something up to the present can be a reliable indicator of its continued existence and relevance in the future. The underlying principle is that longevity signals a certain resilience against factors like change, becoming outdated, or competitive pressures, thereby enhancing the likelihood of its persistence over time. According to this effect, the risk of extinction diminishes as time progresses. In mathematical terms, the distribution of lifespans under the Lindy effect aligns with a Pareto distribution, indicating a specific pattern of survival probability that favors older entities1.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb expanded on this concept in his book Antifragile, distinguishing between perishable and non-perishable entities and how time affects their survival. The core idea is that the longer something non-perishable exists, like a technology, an idea, or a company, in this case, the longer it's likely to continue existing. This principle inversely applies to perishable things, such as humans, whose life expectancy decreases with age. Borrowing from the book example:

“If a book has been in print for forty years, I can expect it to be in print for another forty years. But, and that is the main difference if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print for another fifty years. This, simply, as a rule, tells you why things that have been around for a long time are not "aging" like persons, but "aging" in reverse. Every year that passes without extinction doubles the additional life expectancy. This is an indicator of some robustness. The robustness of an item is proportional to its life!”2

The mathematical formulation of the Lindy Effect, as presented by Taleb, revolves around the concept that every additional year an entity survives, it effectively doubles its future life expectancy. This heuristic illustrates a direct correlation between an item's robustness and its lifespan. It aids in understanding how businesses, technologies, and ideas can exhibit resilience and potential longevity.

Lindy’s Effect on Venture

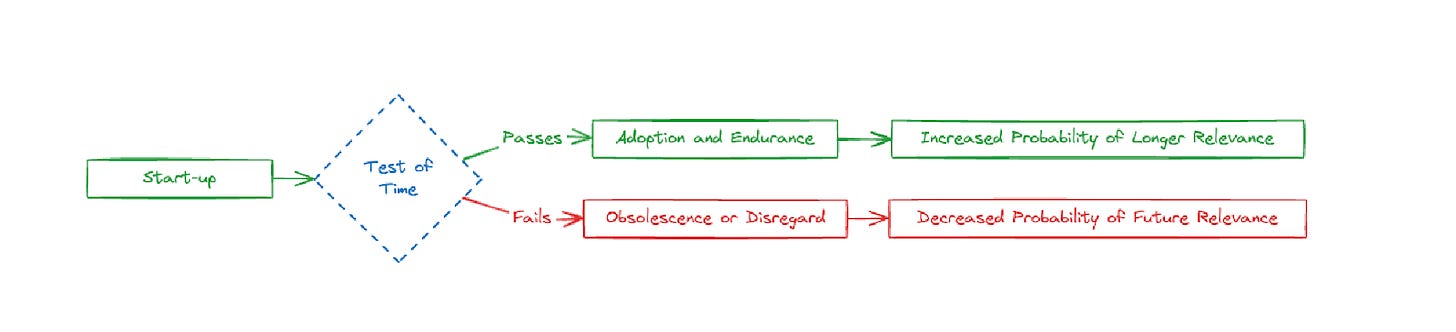

Applying the Lindy Effect to venture-backed startups introduces a fascinating perspective on their potential longevity. However, it's important to note that the Lindy Effect is not a foolproof strategy for predicting the success of startups. Other factors, such as market conditions, competition, and the quality of the product or service, also play significant roles

(randomness). The Lindy Effect can provide a valuable framework for understanding the potential resilience of startups, but it should not be the sole basis for investment decisions. To illustrate this further, consider a buyer from a large enterprise leaving an incumbent solution and being in charge of assessing features for a new startup with little difference in the product suite. Would you feel more comfortable buying from a startup that has raised $4M or $40M? This is one of many variables in the buyer’s consideration and does not holistically consume the entirety of the decision.

The Lindy Effect's applicability to startups is nuanced. For startups, initial survival through significant funding rounds may signal robustness against market volatility and operational challenges. As with the original Lindy Effect, which posits that the longevity of non-perishable things (like ideas or technologies) increases with their age, a startup that continually adapts and thrives past its early vulnerable stages could be deemed more likely to endure and succeed (e.g., find PMF). As with the most competitive markets early on in a venture-backed cycle, perhaps the strongest of strategies is to raise or, conversely, bootstrap your way into your destiny, where you can be around longer to increase your chances of success (exponentially). I’m certainly not advocating for significant raises as I truly believe everything is random and nuanced when it comes to surviving the early-stage chaos, but providing a framework of how absent any differentiation, some startups tend to succeed with a bit of luck and grit to stay alive until the odds tip in the right direction.

In the same vein, it’s essential to understand that the Lindy Effect is a probabilistic, not deterministic, framework. It suggests trends and probabilities rather than certainties. For startups, this means while historical survival and adaptability are positive indicators, they are not absolute predictors of future success.

In any probabilistic structure, this also increases the chances of complete failure and obsolescence. Again, the notion of the Lindy Effect is just one variable or framework for predicting the outcome of startup success. With anything, especially startup success, all the variables must be taken together to actually understand the perceived chances of defying the odds, that is, surviving long enough while not becoming obsolete.

The Lindy Effect offers a valuable lens through which to view the potential longevity and resilience of venture-backed startups. Those who have navigated the early stages of growth successfully, mainly through significant funding (or bootstrapping) and adaptation, are better positioned to continue thriving.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindy_effect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antifragile_(book)